Introduction

Beaver Hats to Hockey Pads was originally published as an essay accompanying the exhibition I curated about felt for the Textile Museum of Canada in 1999-2000. This version has been edited and expanded to form a series of twelve posts that is not so much a chronology as it is a collection of stories that uses felt objects from private and public collections to illustrate aspects of Canadian history from the fur trade though popular culture.

Felt was complicit with colonialism, driving the early days of trade through European millinery. Felt grew with industrialization and manufacturing side by side with steel, peaking through World War II and the subsequent wave of optimism in North American engineering and design. Felt struggles through globalization, but continues unrivalled in some industries, remaining contemporary in quality and sustainability.

Felt is an ancient material, but this is a new-world history that traces the material culture of modern manufactured felt in a North American context. It is at once a series of cliches and a story of survival as felt is worn through use, through weather and through time. KW

-

Hats: Canadian classics, and how some indigenous folks stick it to the man…

-

Wilderness Tips: Capitalizing on the great outdoors, and how an old felt hat can save the day…

-

A Story of Immigration: To the Prairies where felt is good for the sole…

-

First Nations: A museum artifact tells a story of oppression and survival…

-

Industrialization: Where steel is found there is bound to be felt…

-

American Influence and Affluence: cars, white-goods and poodle skirts…

-

The Golden Age of Hockey: Inspiration is found in a harness shop…

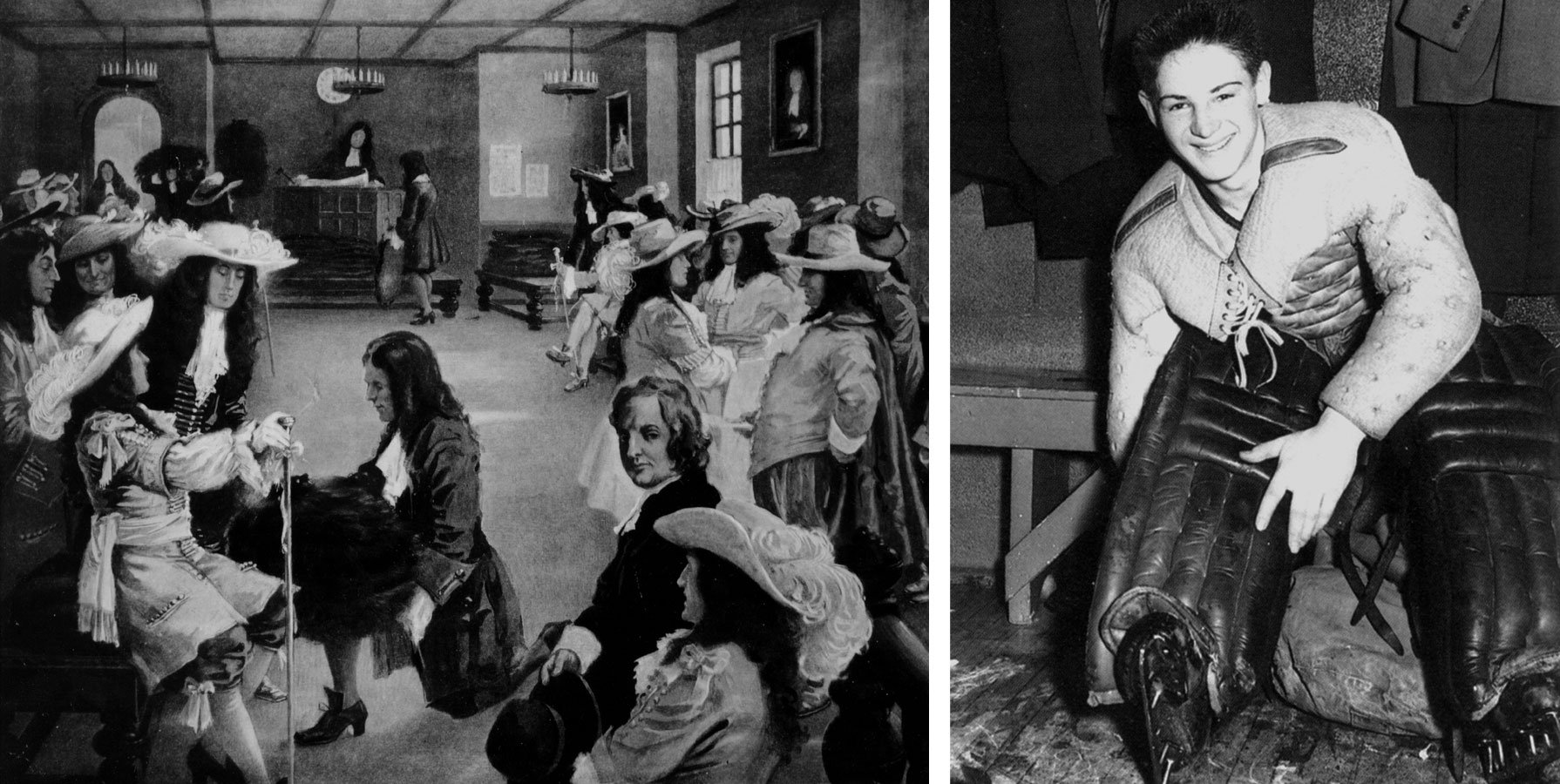

Left: The First Public Sale of Furs, 1672. The traders wear beaver hats in the cavalier style popular throughout Europe in the 17th century (Hudson’s Bay Archives, Provincial Archives of Manitoba). Right: Terry Sawchuck, widely known as one of Canada’s greatest goal-tenders. Here, in 1947, he wears shoulder pads made of felt (The Imperial Oil Turofsky Collection, Hockey Hall of Fame).

1. Pelts and Felts

A vagary of fashion that was the success of us and the death of many long before Confederation…

A beaver hat, or castor in French, is a felt hat made from the short downy fur of a beaver’s undercoat, and was a well-established fashion in Europe during the 1500s. Its popularity grew with the abundant supply of beaver “discovered” in the New World, and became highly regarded as a symbol of power and wealth, made from the finest of felts.

Beaver pelts worn by the Northern First Nations were the most prized of all because the coarse guard hairs, which would otherwise have to be removed before felting, were worn off from use. These called “made-beaver” or “castor gras”— an adult beaver pelt prime in quality and condition— became the unit of exchange for European goods through the fur trade.

In England, labour was organized around processing pelts, and The Worshipful Company of Felt-makers was established in 1629 to regulate increasing trade. The French and English competed for profits in the co-called “new world,” making alliances with indigenous peoples who they depended upon for their supply and survival. Ultimately The Hudson’s Bay Company, founded in 1670, with the privilege of colonial power endowed by virtue of Royal favour, achieved a monopoly over the land from Hudson’s Bay to the Rocky Mountains.

The fur trade laid the foundation for Canada’s development, but was devastating to the First Nations’ ways of life. The cavalier-style beaver hat, favoured by the early traders, represented the spirit of the times. KW

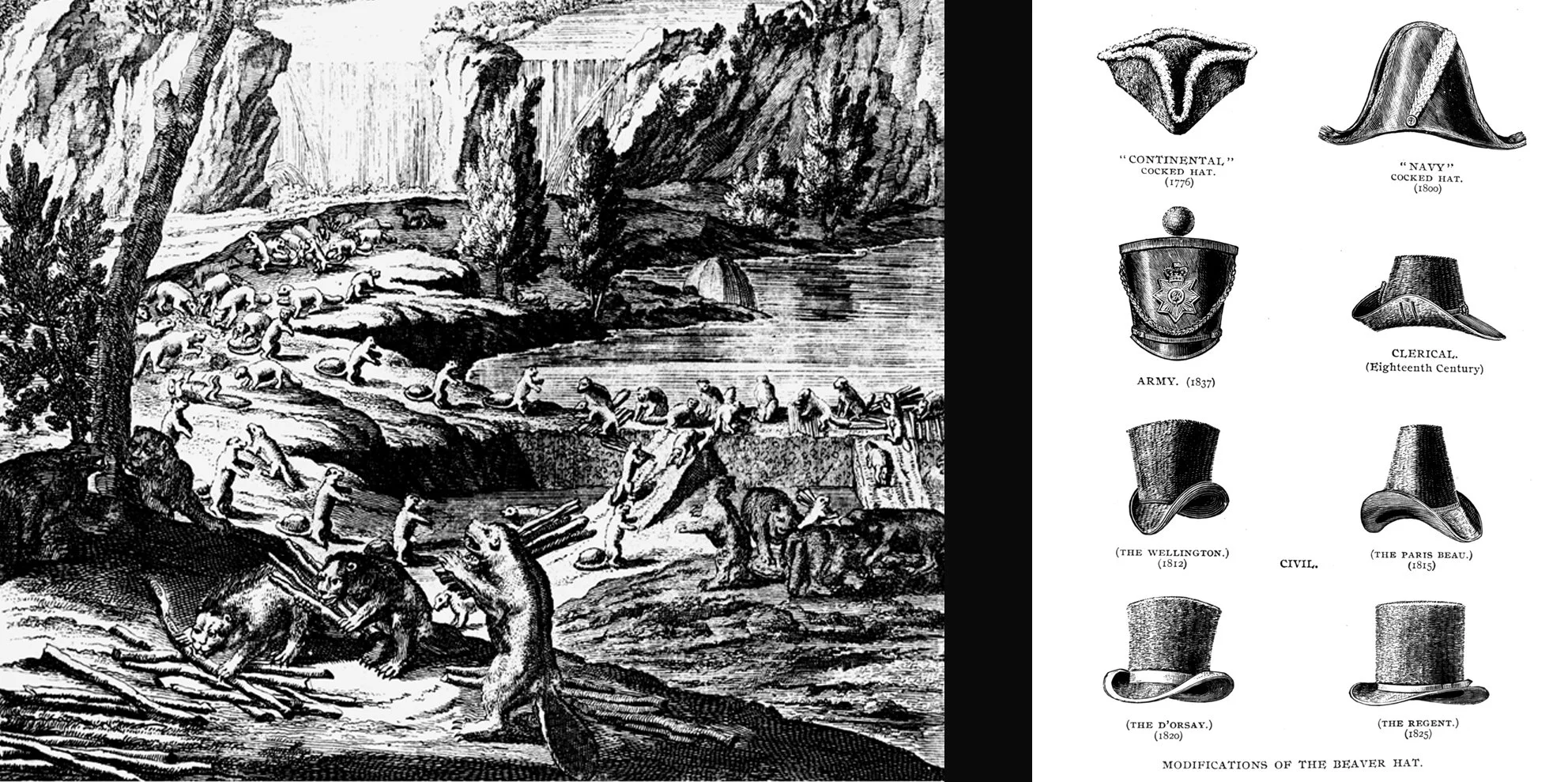

LEFT: image of beavers from the map of “The Dominion of Great Britain on ye Continent of North America” by Herman Moll, 1715 (National Archives of Canada); RIGHT: Modifications of the Beaver Hat

2. Hats

Canadian classics, and how some indigenous folks stick it to the man…

The beaver hat remained all-the-rage through the seventeenth and eighteenth century, shape-shifting according to political change and public fancy. A growing scarcity of beaver contributed to a decline in trade by the 1830s. However, by this time in North America, other felt hats, usually made from rabbit fur or wool, were adopted for purpose and necessity. Soldiers and frontiersmen appropriated the Mexican-style wide-brimmed hat for travel by horseback and exposure to weather. In 1860, John B. Stetson banked on this demand and established what would become America’s largest hat manufacturer, famous for the cowboy hat. In 1919, Smithbilt hats was founded in Calgary giving Stetson a run for its money by providing a cowboy brand favoured by Western Canadians.

The campaign hat, a variation on the cowboy hat with a high crown pinched symmetrically at the four corners was adopted by the Northwest Mounted Police (now the RCMP) in the 1870s. The original pillbox hat, a British model, did not cut it on the Western frontier. The “Mountie” hat was made in the US by Stetson until the company opened a factory in Brockville, Ontario in 1930. In the 1970s Stetson divested from manufacturing, and Biltmore Hats in Guelph, Ontario acquired the license to make the famous hat to this day. However, they are no longer made in Canada. Biltmore, founded in 1917, went into receivership in the early 2000s, and moved South when it was bought by the hat giant Dorfman-Pacific in 2010. The brandname Biltmore remains, celebrating its centenary in Texas, USA. Meanwhile, felt no longer has monopoly over the headgear of the RCMP. In 1990, Sikhs claimed turbans as an alternative to the classic felt, and since 2016 Muslim women in the RCMP can wear the hijab.

Felt hats have been modified by the First Nations since the early days of trade. The people of the Plains revamped them by cutting off the brim. With disregard for the style of hat, they tossed the brims and kept the caps as useful supports for war bonnets. The felt caps are already shaped to the head and easy to cut and sew. This transformation prevails to this day, taking quiet revenge on a fashion trend that undermined indigenous cultures for centuries. KW

LEFT: “Boss of the Plains” cowboy hat, Stetson; CENTRE: Plains war bonnet, loan from Woodland Cultural Centre; RIGHT: R.C.M.P. “Mountie” hat, Biltmore Hats

3. Wilderness Tips

Capitalizing on the great outdoors, and how an old felt hat can save the day…

Filtering is a primary application for industrial felt. In fact, the word felt in German is filz which also means filter. Felt is made in numerous shapes and sizes for filtering a range of substances, due to the properties of high permeability, fluid flow rates and ability to capture large amounts of debris. Felt determines the tone and texture of maple syrup through filtering. When sap is boiled, minerals that are naturally present are concentrated into a substance commonly known as sugar sand which is filtered out through felt to achieve desired syrup consistency.

Even an old felt hat is a filter, and can be used in an emergency. If water gets into your gas, a common occurrence amongst anglers and outfitters, pour the mixture into the hat. The fuel will pass through while the water remains in the cap.

LEFT: “Mecanix Illustrated: The How-to-do Magazine,” 1954; RIGHT: maple syrup filters and cone, made by The Brand Felt Ltd.

The Brand Felt Ltd. manufactures and sells a broad range of industrial felts. It has survived globalization and thrives in Mississauga Ontario as the last remaining pressed wool felt manufacturer in Canada.

LEFT: Knapsack, 1960s, canvas with leather and felt straps; RIGHT: 1) Tobacco pouch, 1990s, hide and felt with beadwork, hand-made at Six Nations; 2) Canteen with felt cover, 1940s; 3) Coleman stove, 1950s, with felt filters and funnels, 1950s and 90s. The original aluminum funnel stamped with Made in Canada is no longer made, and has been replaced by the red plastic counterpart.

Coleman, well known amongst campers, has been a name brand in outdoor recreation in Canada for decades. This American company, founded in 1900 and established in Wichita Kansas, had operations in Canada in the 1920s to expand their markets, and benefit from Canadian policy. The British Commonwealth gave preferential tariffs and duties to products made in member nations. Coleman manufactured products in Canada until the mid-1990s cashing in on ‘The Great Outdoors’. However, beginning in 1998 Coleman succumbed to a series of corporate mergers ending up as one of many trademarks owned by Newell Brands with most products now being made in China. KW

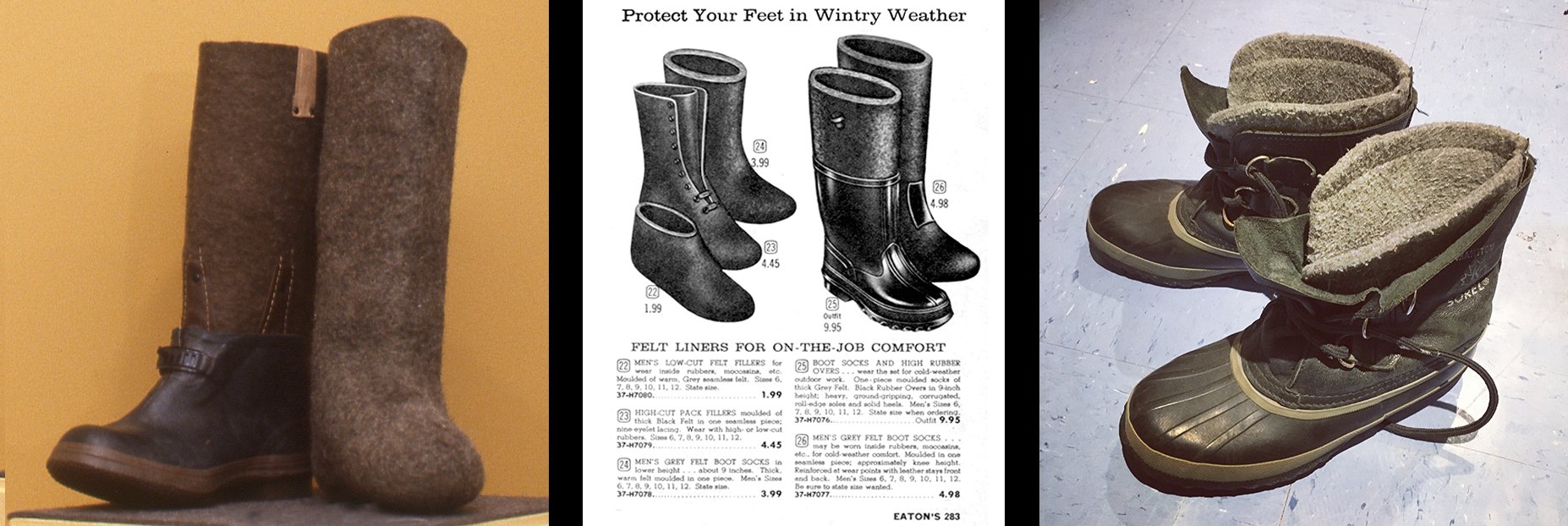

4. Boots

A Cold War, in which felt meets rubber…

Russia has long been a leader in felt-making, especially of molded felt boots called Valenki with some thirty-six million made for the Red Army. Soldiers gave these boots more durability by cutting old tires to the shape of the sole and attaching them by wire over the boot. American companies improved upon this design idea by fabricating rubber galoshes to fit over their molded felt boots.

LEFT: Valenki 1930s made in Russia and American Work Boot 1930s manufactured by B.F. Goodrich Co. Collection: Bata Shoe Museum; CENTRE: Winter boots from Eaton’s catalogue 1963; RIGHT: Sorels – Manitou Classic 1990s rubber and leather boots with felt liners

Canadians made the combination of felt and rubber world-famous in boot manufacturing. Kaufman Rubber (founded in 1907, later known as Kaufman Footwear) and The Rumpel Felt Company (founded in 1912) operated side by side in industry and across the street from one another in Kitchener, Ontario (formerly Berlin, Ontario).

Kaufman is well-known for creating the popular Sorel line of winter boots, a brand made only in Canada until, struggling to compete with cheap imports, the company declared bankruptcy in 2000. The American-based Columbia Sportswear, purchased the trademark and now outsource production mainly from China.

The Rumpel Felt Company made the felt liners for Kaufman boots. George Rumpel, a shoemaker who emigrated from Germany in 1868 would come to be known as the “Felt King of Canada.” He originally bought The Berlin Felt Boot Company in 1879, but after a sojourn with his sons studying advanced felt-making back in Germany, he returned to his new home to grow his namesake business, manufacturing a wide range of industrial felts. The Rumpel Felt Company was the oldest and longest-running felt factory in Canada before closing its doors in 2007. KW

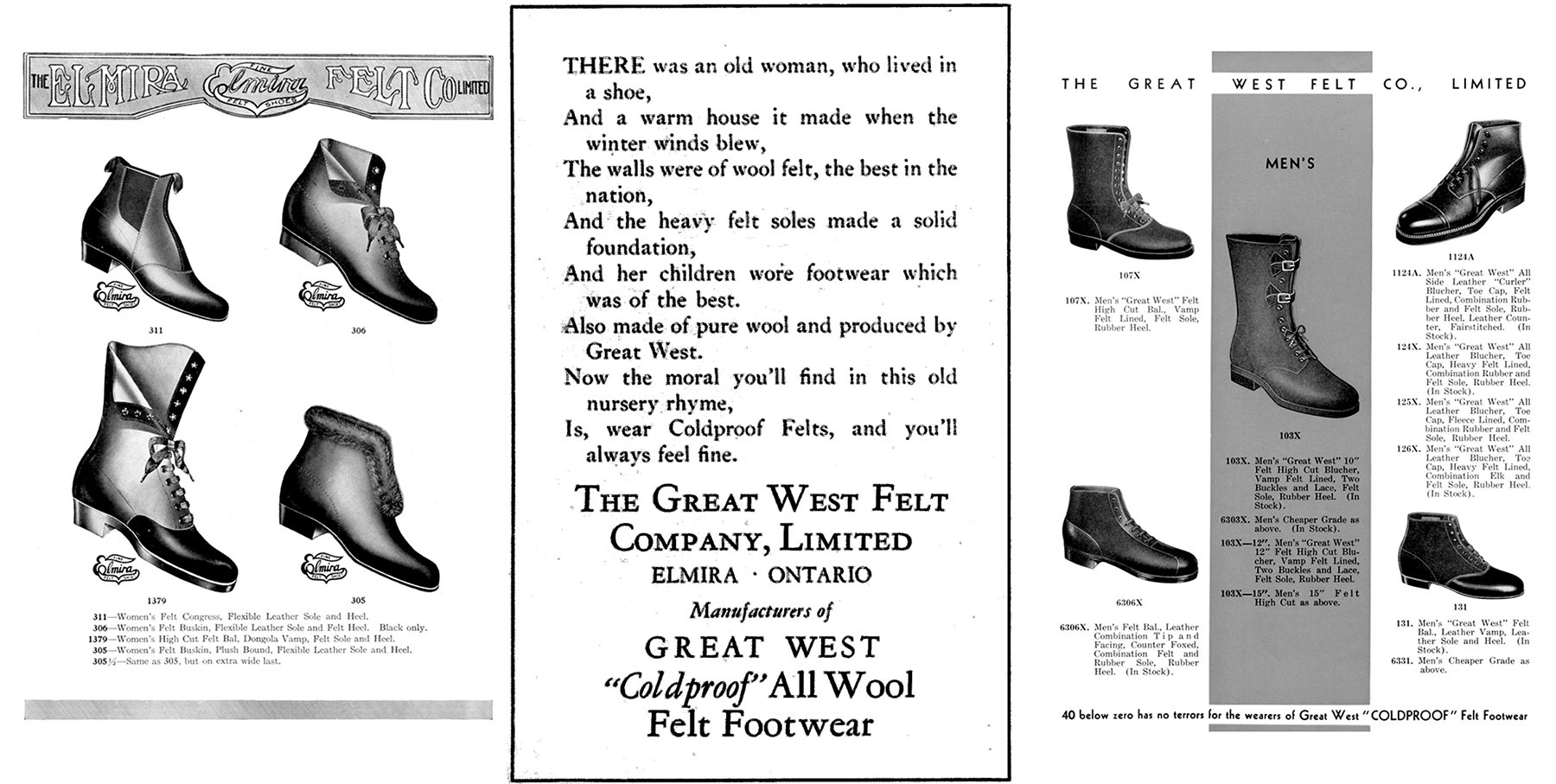

5. A Story of Immigration

To the Prairies where felt is good for the sole…

Through the late-ninteenth century Canada began in earnest to promote immigration, marketing itself as a land of opportunity, in efforts to guarantee sovereignty of colonial land claims and provide a catalyst to economic growth. Policies favoured British and Northern Europeans but other groups were wooed in order to increase the population.

Ukrainians, the name that Canada applied to all Slavic people from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian regions of eastern and southern Europe, made up a large part of this wave of migration. The promise of farmland drew 170,000 rural poor to Canada’s prairies between 1891 and 1914. They settled across Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta, most as homesteaders, some as domestic workers and wage workers in resource industries. But, the optimism crashed with the outbreak of World War 1 when Ukrainians were classified as enemy aliens, and many were interned in camps even as 10,000 enlisted in the Canadian armed forces.

The Ukrainian migration from oppression under Russian rule to continued hardship in Canada is reflected in a collection of well-worn boots from the Ukrainian Museum in Saskatoon. In the early days Russian Valenki, common in Ukraine, proved to hold up well in the cold dry winters of the prairies while a subsequent wave of migration between the wars saw these settlers adapting to their new home, finding similar warmth and protection in felt boots made in Canada.

Valenki, early 1900s, made in Russia; Men’s boots with felt soles and uppers, 1930s, made in Canada; Women’s boots with felt soles and uppers, 1930s, made in Canada. All above on loan for exhibition from the Ukrainian Museum of Canada, Saskatoon.

Canada built an impressive felt boot industry through the twentieth century, producing and distributing styles for comfort and warmth against the winter cold. Felt was used as boot uppers, and also for the soles. With increasing urbanization felt soles became less practical. Now felt is most common as liners and insoles though most of these, originally made of wool, have been replaced by cheaper synthetic felts. KW

Advertisements for the Great West Felt Co. Ltd, Elmira ON, 1930s

Bibliography: www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca

6. First Nations

A museum artifact tells a story of oppression and survival…

While not as common as melton, stroud or duffel, felt was a trade cloth that is still used by indigenous peoples of North America as it makes an excellent support for beadwork. An historical example of such felt is found on a breechcloth from the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) collection known to have been worn by Bearskin, Chief of the Nekaneet First Nation in Saskatchewan in the 1930s. The beadwork shows Plains geometric patterns and Woodlands style of floral work, reflecting the migration and adaptation of many Cree from Woodlands roots to Prairie settlement.

LEFT: Chief Bearskin’s head dress, brimless felt hat beneath bound eagle feathers, 1930s, Collection of the ROM; CENTRE: Breechcloth worn by Chief Bearskin, 1930s, beadwork on felt, Collection of the ROM; RIGHT: Cree from Nekaneet in the Cypress Hills, Saskatchewan, 1930s with Bearskin (left), Crooked Leg (middle) and Peeper (right) (photo: Glenbow Archives)

The Cree Nekaneet Reserve is centrally positioned in the true high plains region of Saskatchewan. Through the 1800s, the federal government tried to keep the First Nations from gathering in these desirable Cypress Hills, and by 1882 most Cree and Assiniboin were pushed to reserves in other parts of the province. But the Nekaneet band refused to leave even as they were destitute. In 1913 the government gave them a reserve, but not until 1975 were they provided with the Treaty benefits they’d been denied for almost a hundred years. According to ROM curator Arni Brownstone, in 1930 the Museum paid $50.00 for the above-pictured garments to a rancher who traded them with Bearskin for food.

The Nekaneet First Nation is now a member of the Federation of Sovereign Indigenous Nations, committed to protecting Inherent and Treaty rights since 1946. KW

7. Industrialization

Where steel is found there is bound to be felt…

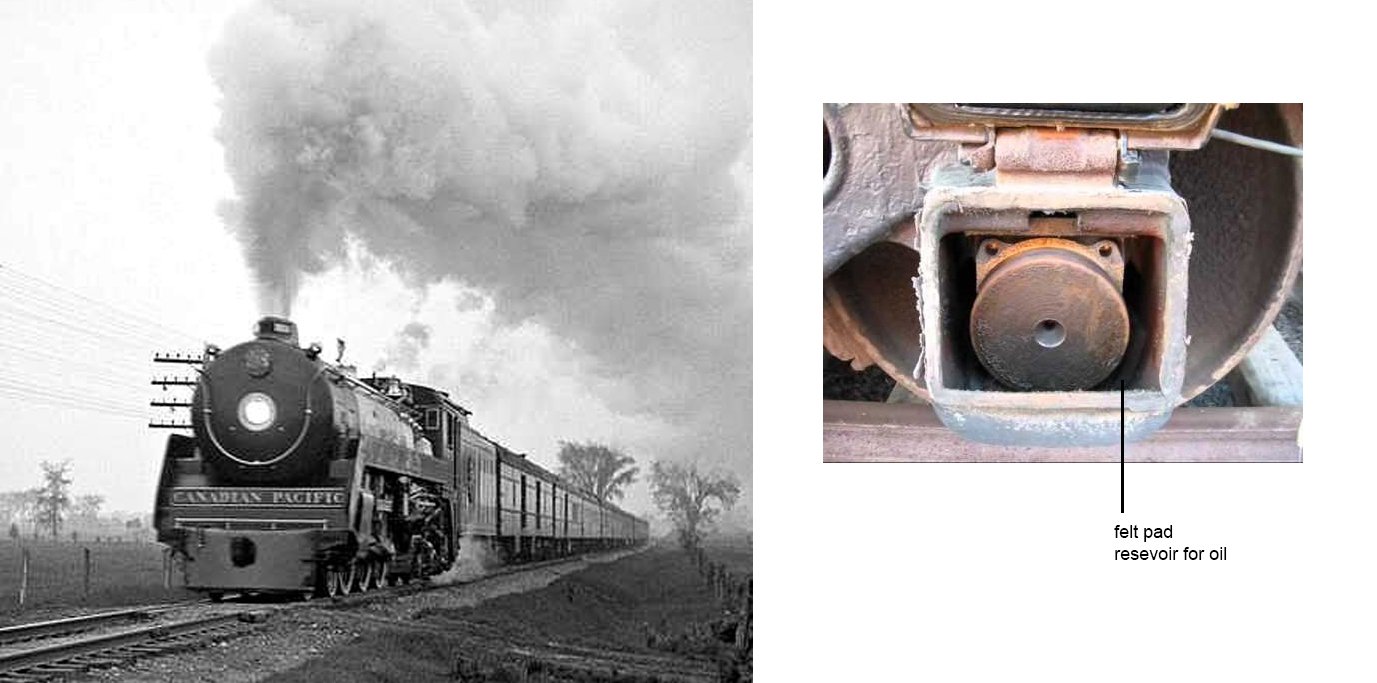

Felt has numerous and wide ranging industrial applications, often playing vital roles in inconspicuous places. The capillarity of felt allows it to act as a reservoir and distributing agent for liquids such as oils for lubrication. Some felts can absorb up to four to five times their own weight. This coupled with resistance to high temperature makes it especially good for high friction areas. During the early days of railroading, felt was there, crossing the country from coast to coast, found in journal box bearings located in the wheels to keeping them rolling smoothly.

LEFT: Canadian Pacific steam engine train, 1930s; RIGHT: journal box

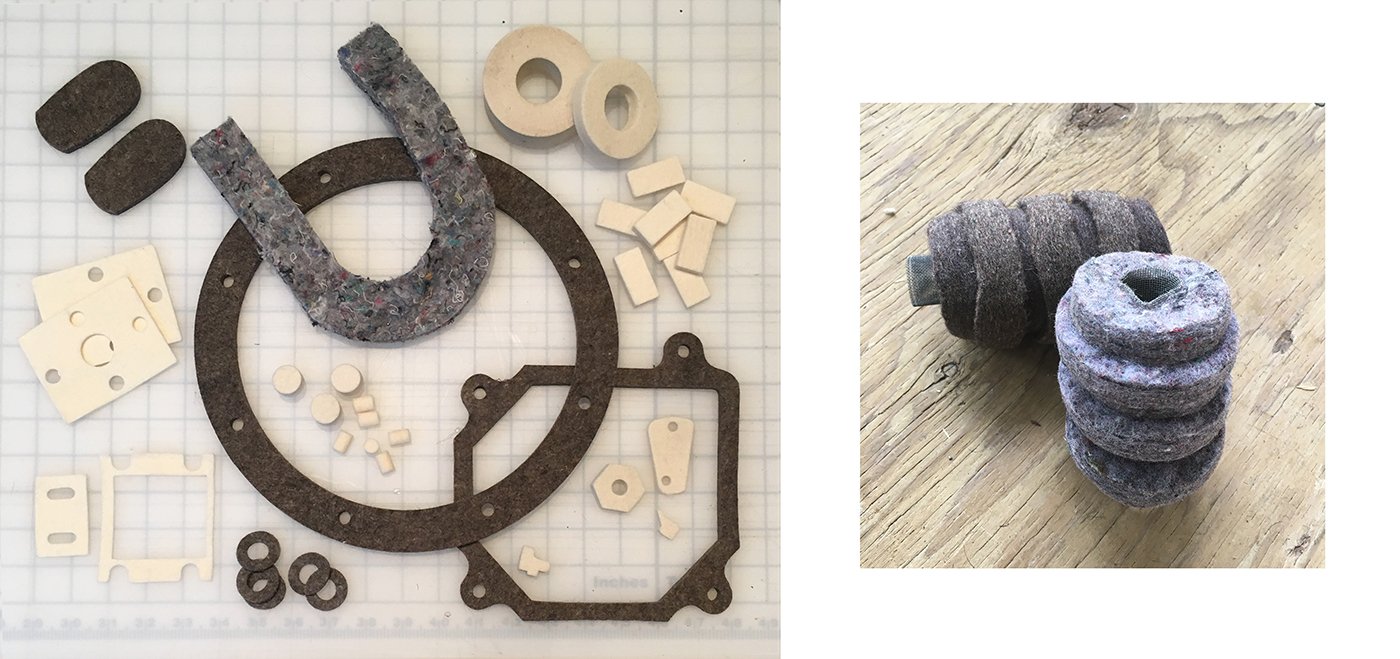

Over 100 different industries have been consumers of felt with over 30,000 applications. These include, but are not exclusive to, shock absorption, vibration isolation, padding, lining, cushioning, packaging, polishing, sound absorption, thermal insulation, lubricating and wicking.

Felt does not fray and so can be die-cut into infinite shapes for machine parts such as gaskets and washers. And miraculously, felt can be both a filter and a seal as it can be processed to a range of densities from soft batting to an impervious firmness comparable to wood without aid of binders. The ability to adjust hardness, elasticity and absorbency in manufacturing has made felt an exceptional engineering material. KW

LEFT: wicks, reservoirs, air filters, fuel filters, polishers, gaskets, washers, seals, vibration dampers, bearing lubricators; RIGHT: appliance filters

8. The Military

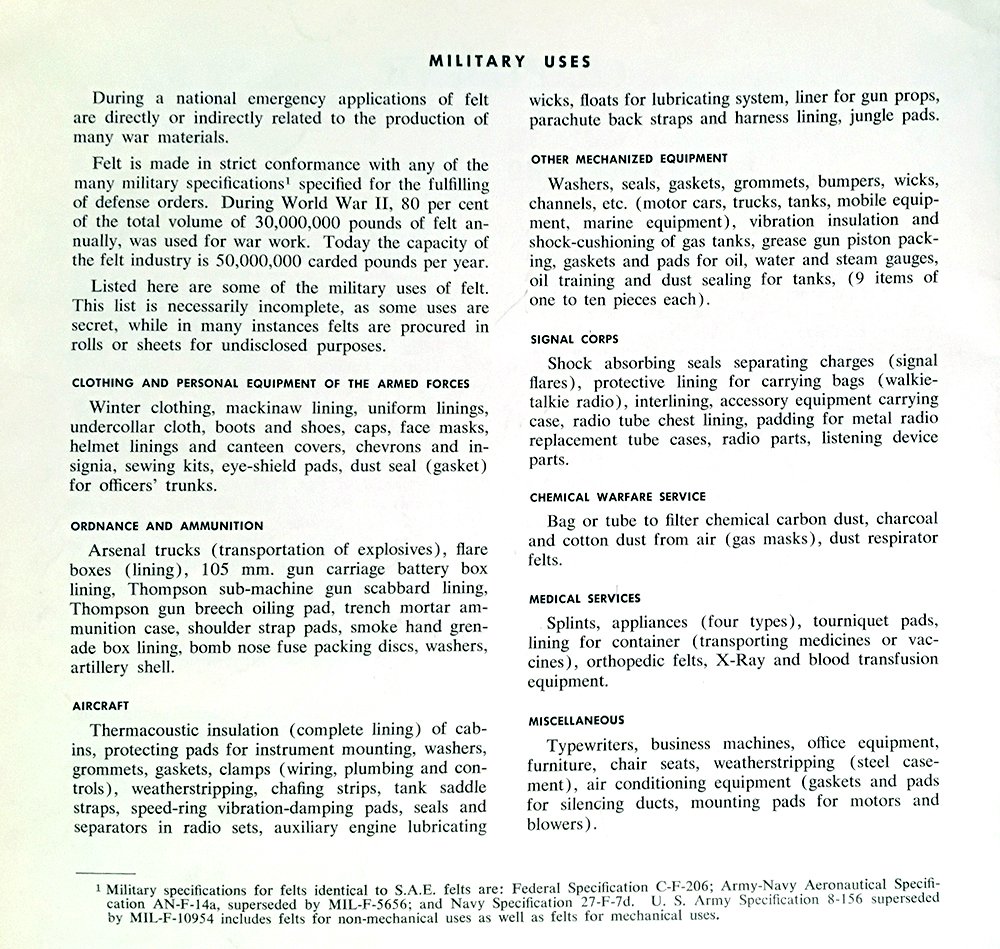

Ordnance and ornament…

With all its industrial applications, felt production peaked during wartime. During WWII most felt made in Canada was sold to the United States when the felt industry in general turned all but a minor part of its production into the war effort with increasing demand. In 1942 in North America, felt output doubled from 1940, and 90% (more than 33 million pounds) of felt went into the allied war machine for a broad range of uses from behind the scenes to the front line with most being manufactured for armaments and ammunitions. The following list published by the American Felt Company in 1951 best summarizes the extent of its use:

LEFT: WWI helmut and canteen with green felt covering denoting Army; WWI crest from 215th Infantry Battalion, screen-print on felt; WWII wedge cap, felt in artillery colours (all items from the collection of the Canadian Military Heritage Museum, RIGHT: felt wadding and shells.

9. American Influence and Affluence

cars, white-goods and poodle skirts…

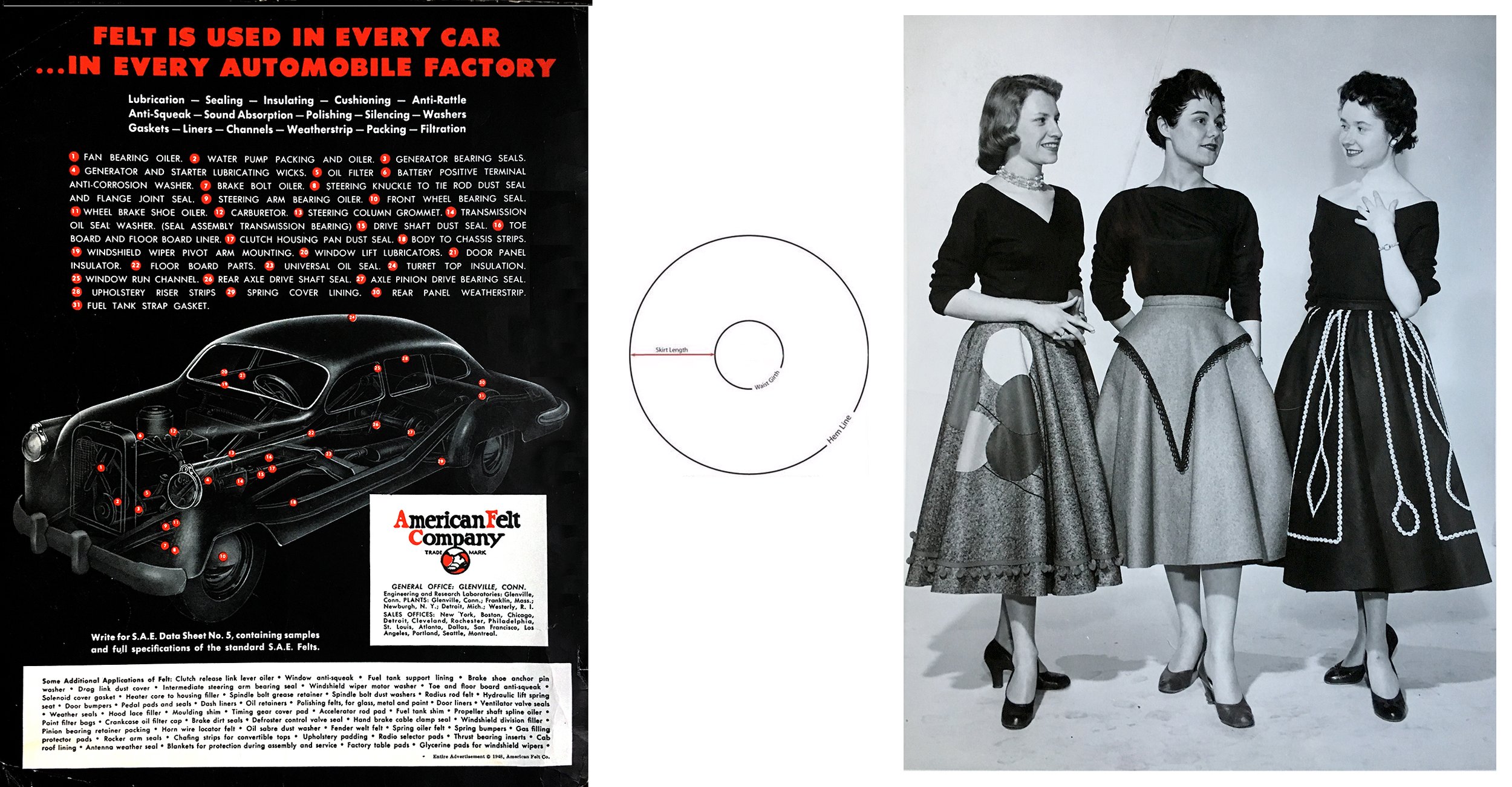

The felt industry in North America came into its own with the advent and growth of the automobile industry. As heavy volume buyers with a demand for precise specifications, car companies drove the need for standardization in felt manufacturing. Standards were determined and defined by the Society of Automotive Engineering in 1923, and remain the basis for the present-day qualities of industrial felt.

Through the post-war economic boom felt remained a strong component of not only automotive parts but also of other modern conveniences flourishing at the time, especially of home appliances or “white-goods”, so-called for their typical white paint or enamelled finish. Felt filters, gaskets and seals became a staple of the American dream, found in dishwashers and clothes dryers across the continent.

Felt found its way into other domestic markets in the 1950s through women’s magazines full of handy tips and patterns. The circle skirt, a full felt skirt often appliquéd, helped to usher in the new wave of growth and optimism in the US, offering a cheap alternative to the voluminous style of ‘The New Look’ made famous by Christian Dior on the runways of Paris. Cut from a circle of felt with a hole in the middle for the waist, American home-makers inadvertently emulated American industry with this pattern that resembles a giant gasket. KW

LEFT: American Felt Company advertisement, 1948; CENTRE: skirt pattern; RIGHT: variations on the felt skirt

10. Inuit

Neevingatah, a unique art form…

Wall-hangings or neevingatah (meaning “something to hang” in Inuktitut) are not as well-known as soapstone carving and print-making, but they follow the same craft tradition in Inuit art, focused mainly in Baker Lake (Qamanituaq).

Like many towns in Nunavut, Baker Lake began as a settlement. The Hudson’s Bay Company opened a trading post in 1916, and soon after institutions such as churches, schools and medical facilities followed, forcing the Inuit to change from a traditional nomadic lifestyle to one of economic dependency.

During the 1950s and 1960s government-sponsored craft programs were established to boost local economies across the North. These were something of a double-edged sword as they fostered creativity and provided work, but were controlled by markets in the South. However, some outsiders were influential in establishing models for Inuit self-governance including Jack and Shiela Butler, who in 1971, helped found the Sanavik Cooperative which has since grown to become an Inuit-controlled business that serves a number of vital functions within the Baker Lake community.

Sewing is an age-old survival skill for the Inuit. For centuries women have transformed hides into clothing and shelter. Felt, like duffel and stroud, was a foreign material introduced to Inuit through the craft programs, and was embraced and transformed through ancient tradition. After making popular items like mittens and socks, the women of Baker Lake used the remnant multi-coloured cloth to illustrate stories through appliqué. These wall-hangings are a unique art form in Canada, expressing tales of adaptation, transformation and survival.

Untitled by Jesse Oonark, image from Pubic Trustee for Nunavut, estate of Jessie Oonark, 1977, all rights reserved

Jessie Oonark, one of the biggest names in Inuit art settled in Baker Lake. She among many, have passed on these new traditions to the next generation. KW

11. Rural Living

On the horse and around the hearth…

At the time of Confederation, 84% of Canada’s population was rural. Though the balance has shifted to a more urban nation since the 1940s, agriculture remains a vital part of the economy.

In the early days when horsepower actually meant powered by horses, felt made excellent padding on saddles and harnesses. It continues to be used by farmers and ranchers today who recognize that felt is superior than synthetic substitutes when it comes to animal well-being. Newer materials may come in many colours, but they trap heat. None compare to the way the wool of felt breathes and reduces heat build-up. Felt wicks moisture away from the horse, and prevents pressure points that lead to sores. And, felt has lasting power, outliving newer materials that break down more readily.

LEFT: saddle with felt pad; RIGHT: felt dress shield, felt hat, harness of felt and leather

Living on the land is sustained by thrift in the home. Penny rugs, often hung on the wall or laid by the hearth, are so-called for their use of circle shapes and low cost. They are made from scraps of found materials, often felt, and old clothes, and usually backed with burlap bags or feed sacks. Penny rugs are common to the Atlantic regions where a larger share of the population lives in rural areas compared to other parts of the country. KW

LEFT: penny rug of felt scraps, 1912, Collection of the Textile Museum of Canada; RIGHT: penny rug of felt, 1930s, fringe made from cut up felt pennants

Felt pennants, 1940s to 70s, made of wool felt. Similar pennants now mark the land in synthetic non-wovens.

12. The Golden Age of Hockey

Inspiration is found in a harness shop…

At the turn of the 20th century when hockey was becoming a professional sport, players wore little in the way of protective gear, but as contact became part of the game, it was essential. In those early days equipment was largely homemade, and displayed the ingenuity of each player.

According to popular belief, Cyclone Taylor, widely revered as hockey’s first superstar, was the first to add felt to his uniform. Inspired by felt-padded horse collars that he saw in a harness shop, he sewed felt onto his undershirt, over his shoulders and down his back. This was initially regarded as an affront to his masculinity, but others soon recognized his wisdom and demand grew. By the 1920s felt had become a common component of hockey equipment in the pants to protect the hips and kidneys, in shoulder pads, shin guards and knee pads.

LEFT: Goaltender, Chuck Rayner gets assistance putting on his equipment. Rayner wears a felt and leather chest pad, and both players are wearing felt sewn onto their undershirts, 1945. photo from The Imperial Oil Turofsky Collection, Hockey Hall of Fame; RIGHT: cricket pads with felt liners were the first goalie pads, 1920s

LEFT: “Kenesky” shoulder pads, 1940s, Collection of the Hockey Hall of Fame. Emil “Pop” Kenesky, a harness-maker come hockey-equipment maker opened his shop in Hamilton in 1926 and became the primary maker of professional goalie gear through to the 1980s; RIGHT: felt crests, 1970s

By the 1960’s felt was largely replaced by synthetic materials. Plastics and fibreglass dominated the market as was the case with much post-war manufacturing. But, team crests remained predominantly felt through the 70s and 80s, and although less visible, felt continues to be used in the tongues of skates. This padding has evolved from the days when hockey players placed two strips of felt beneath their skate laces, enabling them to tighten the fit of the boot to their feet.

LEFT: shin pads of plastic and felt, 1970s; RIGHT: CCM skates with felt tongue. 1990s

CCM and Bauer, the world’s most renowned brands in hockey equipment, were homegrown in Canada. By the 1970s, these company’s fell to corporate mergers, but their names reign supreme. Canada makes for good marketing where hockey is concerned.

Bauer became part of Nike in 1994, and was rebranded Nike Bauer in 2006. This was the first time the American conglomerate used a partner brand on any product. Bauer was sold by Nike in 2008 and has since passed from parent company to parent company all the while retaining the recognizable name.

CCM was one of many companies ultimately bought by Reebok in 2004. Reebok retired all but the CCM brand, but was acquired by Adidas in 2005. Now CCM is the only name brand used by the company on its hockey equipment. In 2017, Adidas sold CCM, and it returned to Canada in the hands of Birch Hill Equity Partners. With 15 partner companies, Birch Hill represents one of Canada’s largest corporate entities. KW